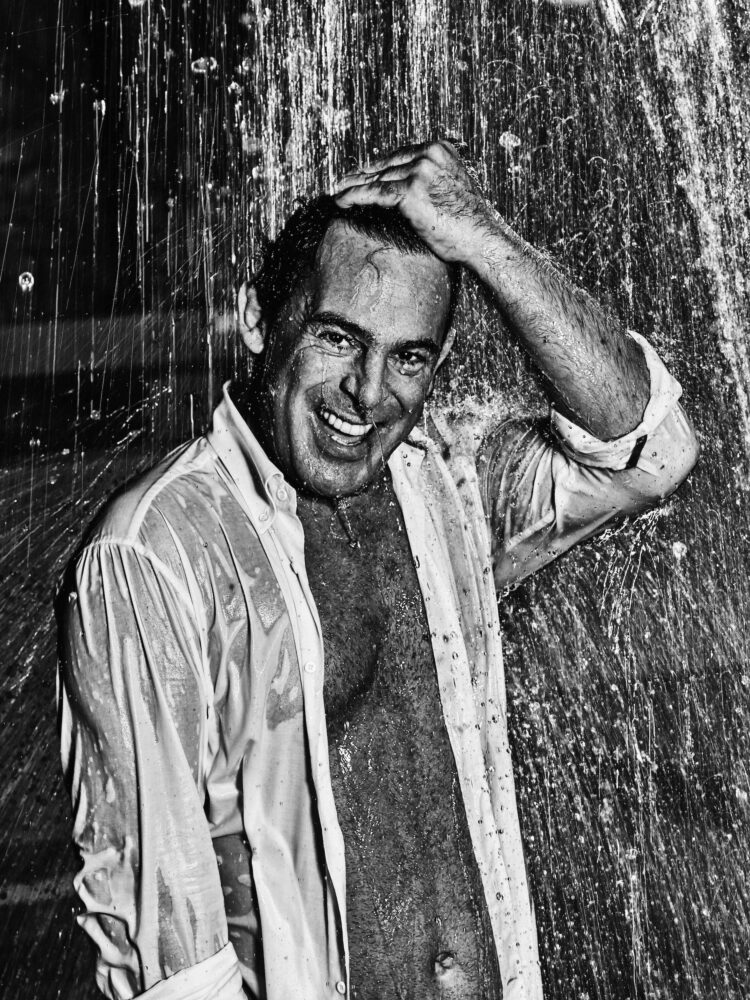

Interview by Veronica Gacia

photos by Steven Lyon

The Mexican son of parents of Spanish blood, he walked from his designated future as the heir of a fortune (his family owns JUMEX, the equivalent pf Doyle Juice in the US) to become a señf made meteor in the art world.

The Hero’s Journey

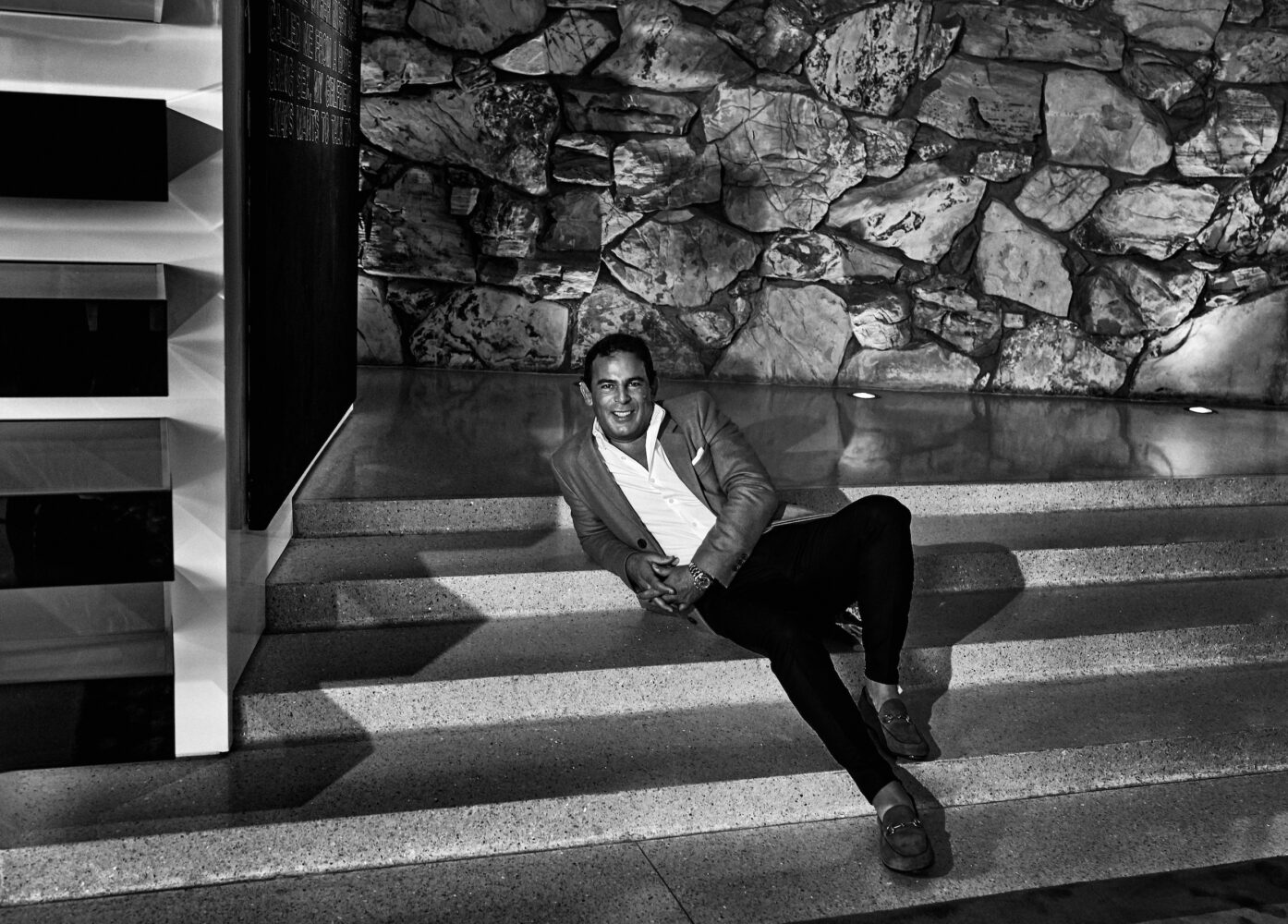

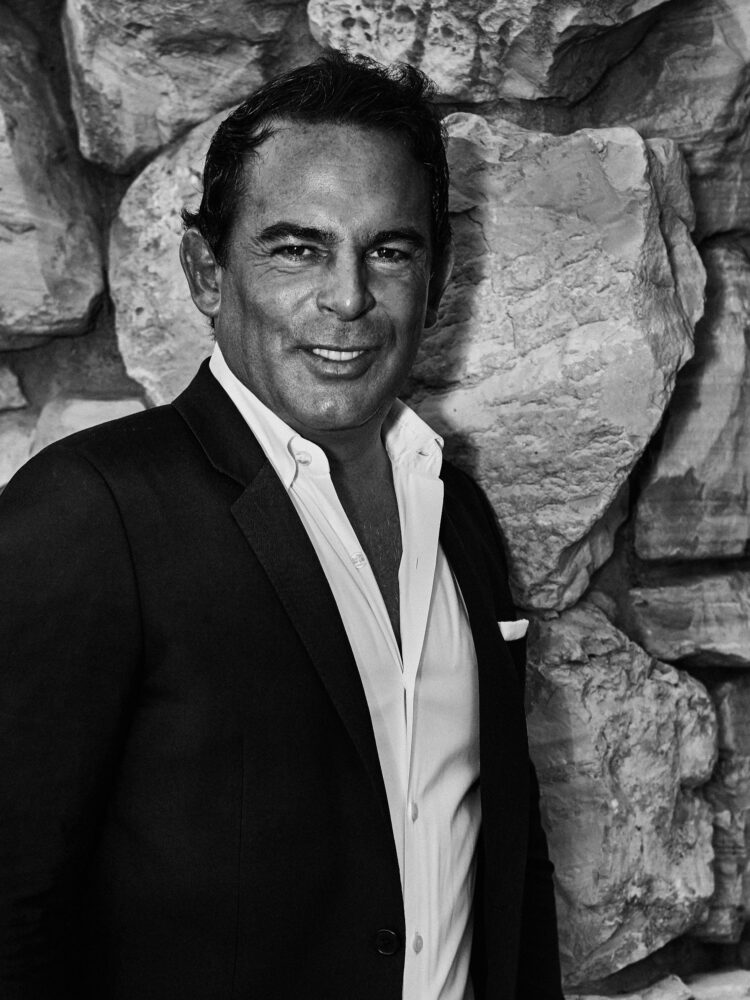

A hero who goes on an adventure, and in a decisive crisis wins a victory, and then comes home changed or transformed. That is the Hero’s Journey and that is the story of Eugenio Lopez Alonso: Scion, rebel, art collector, dutiful son, revered friend. Patron saint of contemporary art and a self made man in so very many ways.

Eugenio is at his prime, his peak, having lived more lives in his 50 years than many in their hundreds put together.

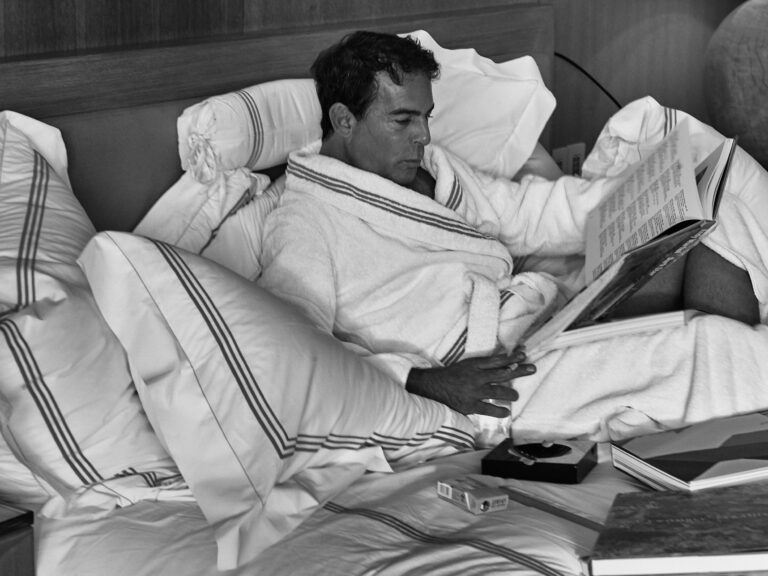

He is as much as home at Blenheim Palace as he is hanging put with his staff, in his pajamas at home.

He likes Beluga and truffles exactly the same as he likes homemade Mexican food.

He has the memory of a Borges character, Funes el Memorioso, and like a Borges character one cannot believe such dualities exist in the same man.

Insatiably curious since childhood he is full of precise dates, names and colors. He will never stop learning, but he will also never stop laughing.

And yet he is not jaded and yet many things still fill him with wonder, like the wonder he felt when he saw his first auction, and saw a painting by Robert Ryman, as his work is, all white and couldn’t quite grasp what all the excitement was about.

But when he heard the price his mind immediately assumed: this must mean something more and we want to know what it is, and almost immediately he went to work and in no time he knew.

He knew this world was like Alice’s world when she stepped through the looking glass. He knew that all his previous notions of aesthetics could not apply anymore and he knew, no, he FELT that this is what he had been born to do.

But why do we call him a hero? Let me count the ways:

According to John Berger, the main consequence of Picasso’s fame was solitude. Eugenio has sacrificed his privacy, his aloneness because of his tock star status in the collecting world. Like Charles Saatchi said : “My aim in life is not the pursuit of happiness as much as the happiness of pursuit.”

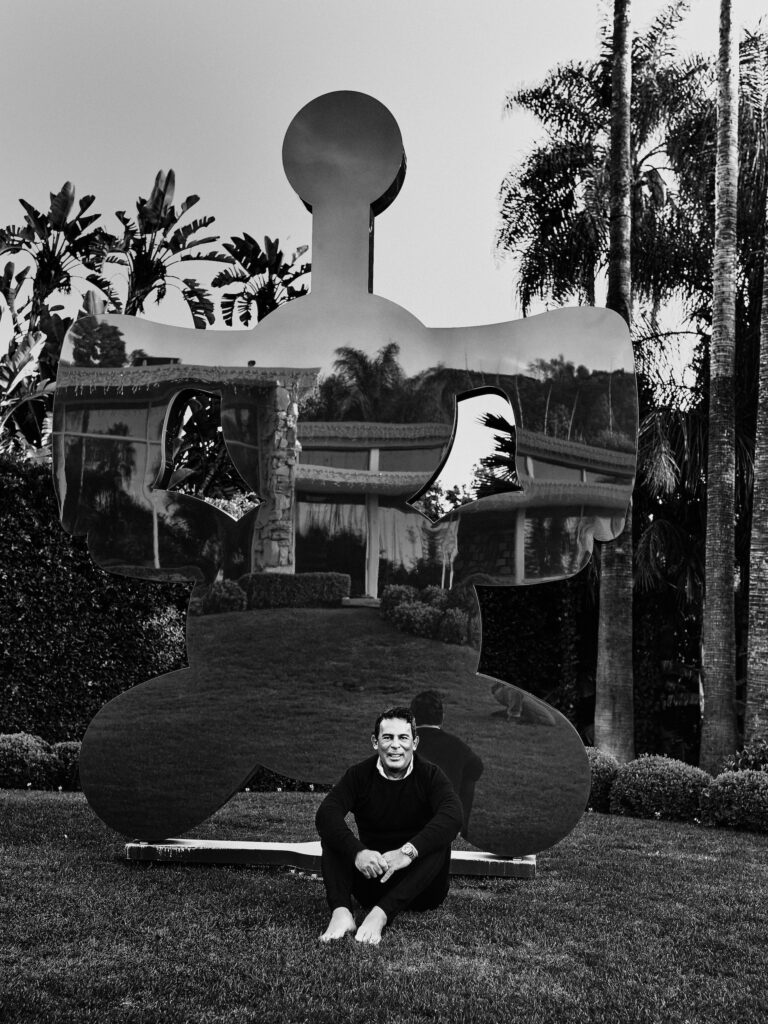

Eugenio López Alonso is a hero because he made the impossible possible: he built a Contemporary Art Museum, through a will so legendary it rivals the giving of fire to humans by Prometheus. There was no governmental support, there were no patronages, there was just his strength of character and his sure footedness.

The majority of museum visitors today do not realize (because they are but rarely told) how radically a painting by Vermeer, Matisse, or Jackson Pollock differs in intention and purpose from the tribal masks, the prehistoric figurines, even the temple sculpture or altar paintings housed sometimes in the same building.

It was indeed a momentous development by which the visual arts were thus lifted above the activities of artisans, however skilled: this emancipation from utilitarian bondage must be credited—over time—to the art collectors.

But the art collector is not to be confused with the equally important patron of the arts. The patron, whether he commissions the building of a temple or a church, or a museum as is Eugenio’s case, or the decoration of a castle, or the illumination of a manuscript was, no doubt, interested in the excellence of the product he hoped to sponsor and to acquire; and thus patrons of art from King Solomon to Pericles, from Abbot Suger to Pope Julius II to Eugenio López were never slow to recognize the outstanding masters of their time and to secure their services, often in the face of fierce competition.

Yet this is Eugenio Lopez’s duality: he is also an art collector who treasures a sample of calligraphy, a fine marble head, or a watercolor and is no longer concerned with the original purpose for which these objects were made; he simply values them as “art.”

NEWS LETTER

FOLLOW OUR JOURNEY![]()